The summer of ’64 brought grief to the Hall family. A letter between sisters sums it up

Article Author: Abigail Koontz (This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail March, 2024)

The summer of 1864 was a tumultuous one for the United States, caught in the throes of the Civil War. The Federal Army employed more aggressive tactics in the South — such as burning private homes and property — and the Confederacy was losing ground.

Locally, the summer of 1864 irrevocably altered the life of 19-year-old Hagerstown resident Sarah Bell (Hall) Matthews, who witnessed the Ransom of Hagerstown and the aftermath of the Burning of Chambersburg.

Sarah Bell Hall was born in Hagerstown on Oct. 6, 1845, to William Hall, a master machinist, and Elizabeth (Noel) Hall. Sarah’s parents had moved to Hagerstown from Pennsylvania by the early 1840s; they had at least seven children together.

On May 30, 1864, the Halls received terrible news. Their oldest son, Noel, a 22-year-old private in Company K, 12th Regiment, Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry, had died from wounds received at the Battle of the Wilderness in early May.

Noel’s body was transported home from Virginia and buried in Rose Hill Cemetery. Sarah had lost her brother, but soon she lost the presence of her older sister, Kate, who married Nathan Wright on June 14 and moved away.

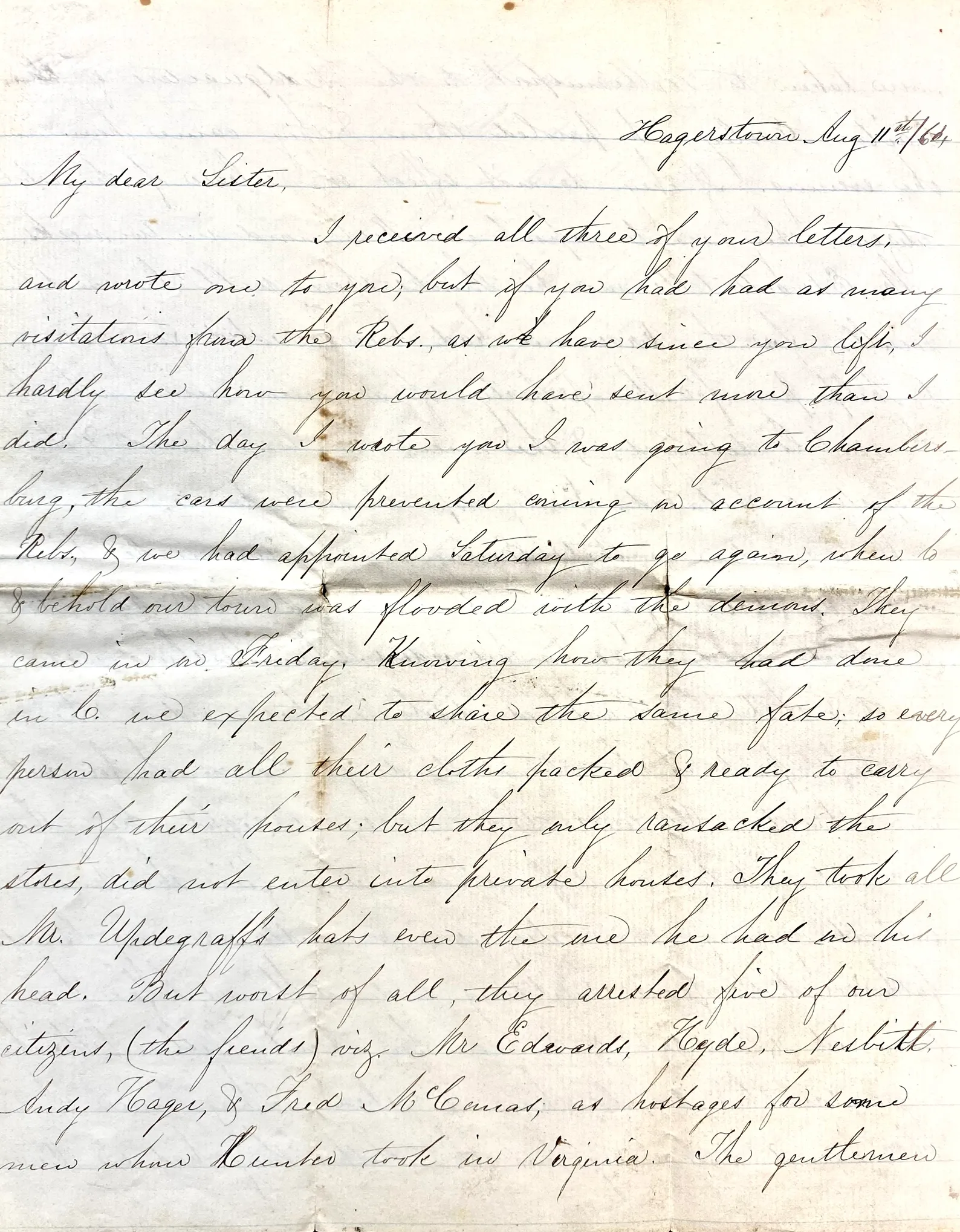

It was to Kate that Sarah wrote on Aug. 11, 1864. “My dear Sister,” Sarah wrote, quickly apologizing for not replying to Kate’s last three letters. “If you had had as many visitations from the Rebs, as we have since you left, I hardly see how you would have sent more than I did.”

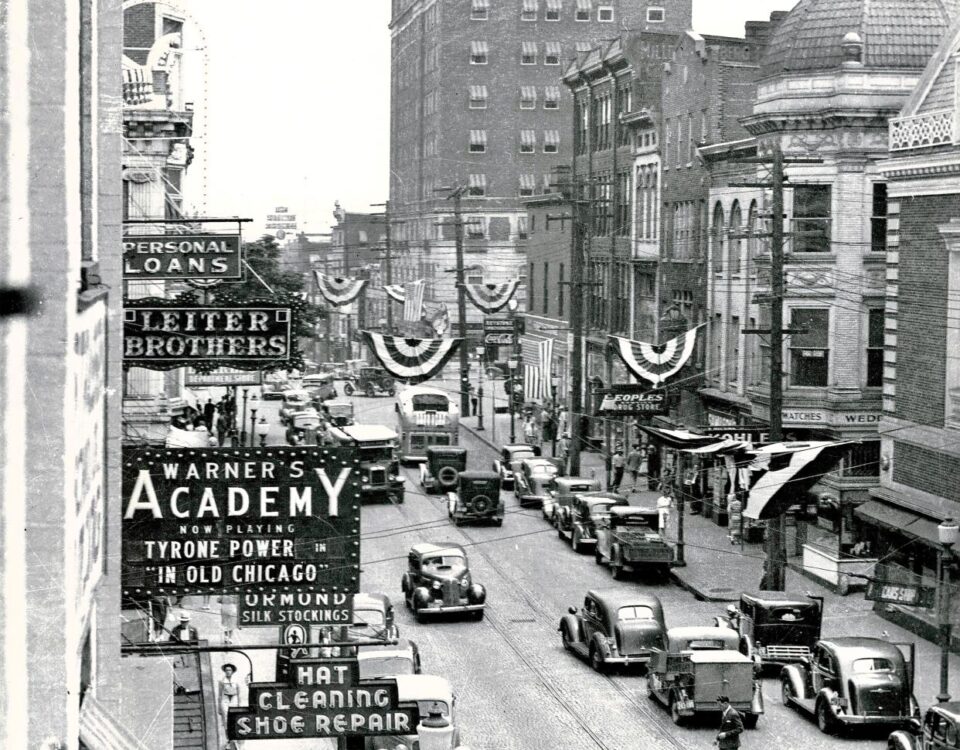

Sarah’s letter captured her turbulent experiences of the prior month. On July 5, 1864, word reached Hagerstown that Confederate Brig. Gen. John McCausland was heading toward Hagerstown. “Every person had all their cloths packed & ready to carry out of their houses,” she wrote, as merchants and even the mayor fled north.

“Our town was flooded with the demons,” Sarah recalled, when McCausland and 1,500 cavalrymen arrived on July 6. McCausland established camp at Town Hall and made his ransom demand. Hagerstown’s citizens had four hours to hand over $20,000 and 1,500 sets of men’s clothing. Failure to comply would result in the burning of Hagerstown, with time for women, children and invalids to be removed.

As Hagerstown’s leaders arranged to meet the demand, Confederate soldiers assembled wagons along West Washington Street to collect clothing, and spread out through the streets.

“They only ransacked the stores,” Sarah wrote, including local hatter George Updegraff’s shop. “They took all Mr. Updegraff’s hats, even the one he had on his head.”

By 8 p.m., Hagerstonians gathered all they could for the Confederates, and the town council raised $20,000 from local banks. With the demand satisfied, the Confederates left Hagerstown.

McCausland sought ransom from five more towns, including Chambersburg, Pa., for $100,000 in gold. Chambersburg’s residents failed to meet that demand, and under orders from Confederate Gen. Jubal Early, McCausland ordered Chambersburg burnt — leaving 500 structures smoldering and 2,000 citizens homeless.

Sarah’s grandfather, John Noel Jr., was the proprietor of The Golden Lamb Hotel in Chambersburg. “Grandfather’s whole front building was in flames,” Sarah described. “Our Grandparents are staying with us now. I spent the day in Chambersburg yesterday; the destruction is terrible … Aunt Willie’s is nothing but a pile of bricks.”

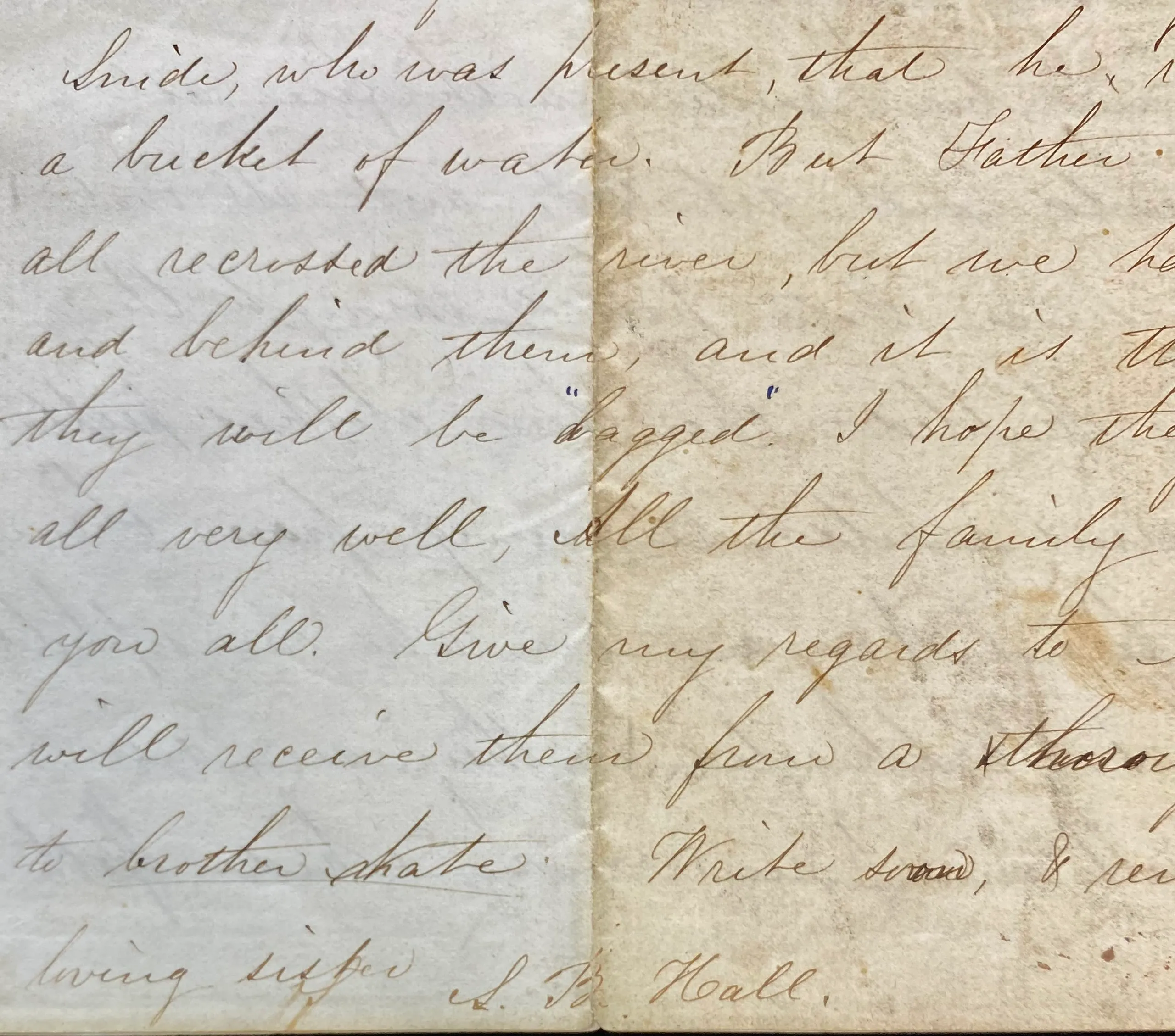

Sarah’s family had one last brush with Confederates who were moving south to recross the Potomac. “Father & Grandfather were sitting on the front porch on Saturday, when three [Confederates] rode up to the door, and one of them roughly demanded a drink … Father told him that there was a spring around the corner, whereupon the impudent scoundrel ordered [Father] to go to it and get him one. But you know father does not generally comply with such demands.”

The incident escalated. “The fellow leveled his gun at [Father] and asked him if he would like his shanty burnt,” Sarah wrote, explaining that Snyder, their brother, finally fetched water.

Sarah ended her letter by wishing Kate’s in-laws well: “Give my regards to Mr. & Mrs. Wright, if they will receive them from a thoroughly union girl.”

After the summer of 1864 ended. Sarah began work as a fourth grade teacher in the Baltimore Street area.

On May 29, 1869, Sarah, now 24, took part in the “Excursion to the Great Battle Field,” a commemorative event for Washington County residents to decorate the graves of fallen soldiers at Antietam Cemetery. As part of the Ladies Committee, Sarah oversaw fundraising and floral decorations.

James Peebles Matthews, 31, oversaw the Transportation Committee, arranging train and hackney rides to Antietam. James, a native of Shippensburg, Pa., a Civil War veteran, was an attorney in Hagerstown and a clerk for the local U.S. Pension Bureau office.

Perhaps it was during planning for the Great Excursion that Sarah and James met; they married on June 22, 1870, and had two children, Elizabeth Margaret (Hall) Adams and Noel Hall Matthews. Sarah named her only son after her fallen brother.

Sarah and James moved their family to Baltimore by 1880, but kept close ties to Washington County. James, an avid journalist and editor, co-purchased the Herald and Torch Light in 1885, incorporating the publishing company in 1891.

Sarah and James lived at 1101 Madison Ave., Baltimore, into later life. Sarah attended St. Peter the Apostle Church, carrying out benevolent work for its Woman’s Guild. She died in 1912 at age 66 and is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery with her family.

Sarah’s letter currently resides in the Washington County Historical Society archives. WCHS will be celebrating stories like Sarah’s during Women’s History Month. For more information, visit washcohistory.org.