Wrapping things up for the New Year

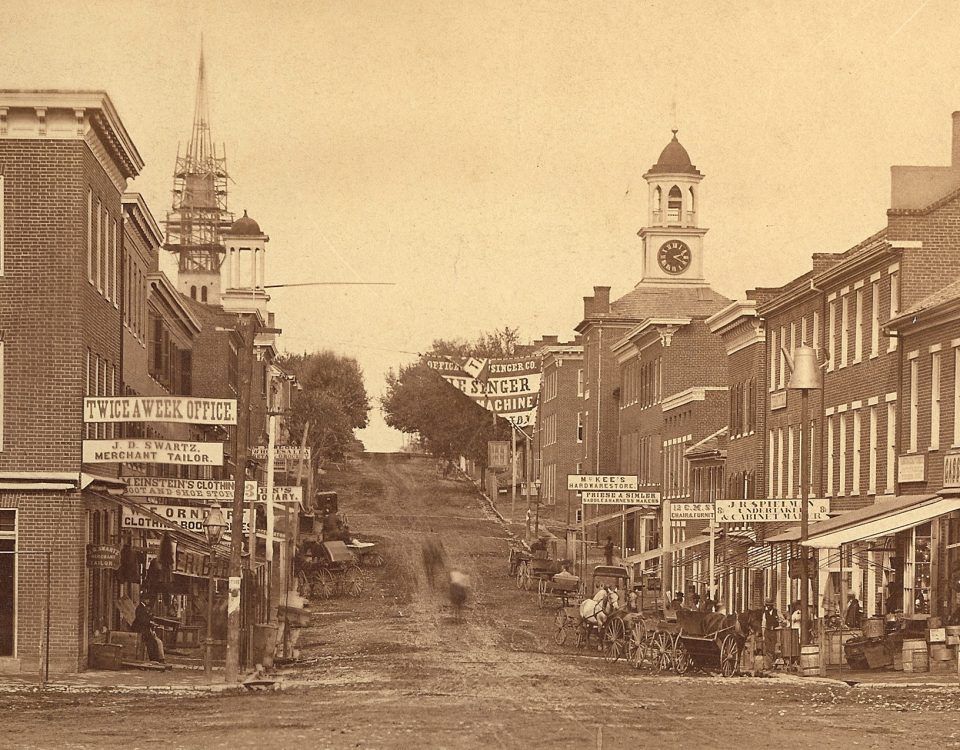

One of the things I most enjoy about being a curator for an historic house is the opportunity I have to share the little details about everyday life in the past with those who visit the museum. Having been privately owned from its construction in 1825 until its donation in 1966, the Miller House is perfect for connecting new visitors with life during the early to late 1800s. As Wi-Fi, tablets, and smart phones become ever present in our 21st century lives, we lose a lot of the contextual knowledge involved in understanding how life worked for our ancestors, and it is crucial that museums now provide that background knowledge. The lessons of the past are only valuable to those who can actually understand and apply them. One of the most effective ways to do this is to build upon connections we still maintain with the past – like the ways in which we celebrate holidays. It is wonderful to be able to point at familiar Christmas traditions like the tree or the stocking and see the interest and comprehension on a visitor’s face as you describe the history behind them.

All of that being said, however, sometimes explaining the history behind popular traditions brings up more questions than answers. This is something that has been particularly challenging this year, when our Christmas tours focused on the early 20th century. While our other tours focus on traditions developed around joy, charity, and family, most of the traditions developed during the early 1900s to convince department store shoppers to ‘buy more.’ This definitely includes my own personal holiday hobgoblin: wrapping paper. I have, like most people my age, a love/hate relationship with wrapping paper. On the one hand, it’s paper that exists only to be ripped up and tossed away, and it’s a major pain to wrap every single last thing I’ve bought for people (that’s why bags exist, right?!) And on a wider scale, it’s extremely wasteful. It’s estimated that we spend over two billion dollars on wrapping materials per year, and all that wrapping paper adds up to almost 4 million tons of trash per year just here in America alone. It seems like wrapping paper should be one of those historical trends, like using real human teeth to make dentures or dumping chamber pots into the street (I’m a riot at parties), that should be firmly in the category of ‘There’s Probably A Good Reason Why We Don’t Do That.’ On the other hand, it is extremely satisfying to open a beautifully wrapped present. Research suggests that there is actually a tangible psychological benefit to both seeing and opening a wrapped present. In fact, studies even suggest that we perceive wrapped gifts as holding more personal value – despite how impersonal the gift inside may be. But why in the world do we wrap things in paper in the first place?

The answer is, like so many other inventions, purely an historical accident. Now, many cultures have historically wrapped presents – ancient Japanese citizens utilized fabric in a reusable technique called Furoshiki. The Chinese, who are credited with the invention of paper, quickly utilized it to create gift-giving envelopes, but never used it to wrap larger presents. But despite the invention of paper in the 2nd century BC, Western cultures did not adapt the idea of wrapping paper until thousands of years later. Some of the first known examples of gifts wrapped in paper come from Victorian England. Wealthy Victorians with the time and money to spend wrapped presents in paper they had decorated themselves with ribbons, lace, and cutouts from newspapers and illustrated ladies’ magazines. At this point, though, wrapping paper was firmly a luxury item. Handmade from rag pulp, paper was costly, and therefore extremely dear to those who could afford it. In addition, the relatively low literacy rates of the time meant that there were not many available sources of paper like newsprint lying around for reuse as wrapping paper.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-1800s that the manufacture of paper became industrialized. In addition to mechanizing the process, chemically paper was now made with tree pulp. These changes greatly drove down the price and increased the ready supply of paper. Advances in printing technology also created the ability for colored printing to be mechanized, instead of being done by hand in workshops. More paper began to be used for a wider variety of purposes, including the protective wrapping of packages in stores. It wouldn’t be long before people began to reuse these thick paper wrappings and create their own decorative paper like previous generations had. And by the time the 1900s rolled around, tissue paper had been invented. This thin, brightly colored paper was used to line boxes from department stores, but was quickly found to be a wonderful covering for presents at all occasions. Once paper manufacturers and stationers discovered the popularity of tissue paper for gift coverings, it began to make an appearance at stationery shops solely as wrapping paper. Manufacturers even began to print tissue paper with decorative images for use year-round.

The use of decorative tissue would inadvertently lead to our modern rolls of wrapping paper. In 1917, a stationery store in Kansas City, Missouri, sold out of their red, green, and white tissue paper. In desperation, one of the store owners put out stacks of highly decorative French paper typically used to line envelopes. The decorative paper was a hit, selling out almost immediately. The store owners bought more the following year, and soon, the highly decorative paper was sold to consumers by the roll. Fast forward 100 years, and we’re using enough paper to lovingly wrap almost 6 football fields each winter holiday season.

And there’s the unwrapped truth – we don’t use wrapping paper for some symbolic, festive reason, it just looks really pretty. If you’re both ecologically and aesthetically inclined, however, you can take ancient history as your guide. Try reusable or recycled gift wrapping options for your next surprise package – it’s an historian-approved solution that will look good and make you feel good!