Article Author: Abigail Koontz (This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail April, 2024)

The American West between from 1865 to 1895 is often painted as the untamed, lawless domain of bandits and cowboys. But did you know that Western Maryland had its own bandits during that time?

Across Washington County, residents of local towns, villages and farms were plagued by the relentless and crafty schemes of horse thieves.

Western Maryland in the early 19th century saw the emergence of turnpikes, railroads and canals, but the most common means of transportation was by foot, horse or horse-drawn transport.

Horsepower touched many aspects of daily life, from individual transport to income. Horses pulled barges, fire engines, mail coaches, farm equipment and hearses; they hauled resources and powered wars.

Because horses were such a necessity, thieves saw a lucrative opportunity, especially in areas like Washington County that still were part of the frontier. Between 1790 and 1804, Washington County newspapers such as The Washington Spy and its successor, The Maryland Herald and Elizabeth-Town Advertiser, published more than 110 notices of horse theft (not counting lost horses).

Victims during this time offered a range of monetary rewards for their horses and the capture of thieves. For instance, in 1791, John Ragan offered a $2 reward for his stolen horse, approximately $67.46 today. Other rewards ranged up to $200.

How much would you offer as a reward if your horse were stolen, leaving you to walk from Williamsport to Hagerstown or waiting for a passing stagecoach?

‘Skulking in our neighborhood’

Eventually, two Washington County residents had enough. On June 8, 1803, Daniel Gehr and John Ragan began organizing an association of county residents against horse theft.

Gehr and Ragan proposed a subscription association in which members paid a fee to the group for mutual support against thievery; subscribers would actively work on detecting local horse thieves.

As Gehr and Ragan advertised, subscribers “will have a tendency to detect all Horse Thieves, and drive all such as are now skulking in our neighborhood to some other part of the world.”

Gehr and Ragan’s proposal met with enough enthusiasm that on Oct. 12, 1803, the Washington County Association for Detection of Horse Thieves was formed, headquartered in Elizabethtown (officially named Hagerstown in 1814).

Other communities across the United States formed anti-horse thief associations to detect, suppress and apprehend horse thieves. These societies often operated on subscription models. They formed their own constitutions, bylaws and regulations, and were even incorporated by local governments.

Despite the formation of the Washington County Association for Detection of Horse Thieves, locals still suffered losses. For example, on a Tuesday evening in January 1805, Jacob Foutz left the warmth of “Mittelkauff’s” tavern in Hagerstown to find his chestnut-colored horse — and all his tack — stolen. He described his horse in painstaking detail in a reward advertisement.

Horse theft was a lucrative but risky business. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, horse theft was punishable by state laws with varying sentences of jail time, pillory time, public lashing and the branding of “H.T.” on the forehead. By the 1830s, suspected horse thieves were held at the Washington County Jail, built by 1827 at the corner of Jonathan and Church Streets.

Horse thieves also formed gangs, preying on local farming communities. They stashed stolen horses in hidden locations until they could be moved outside the county or state, making them more difficult to track.

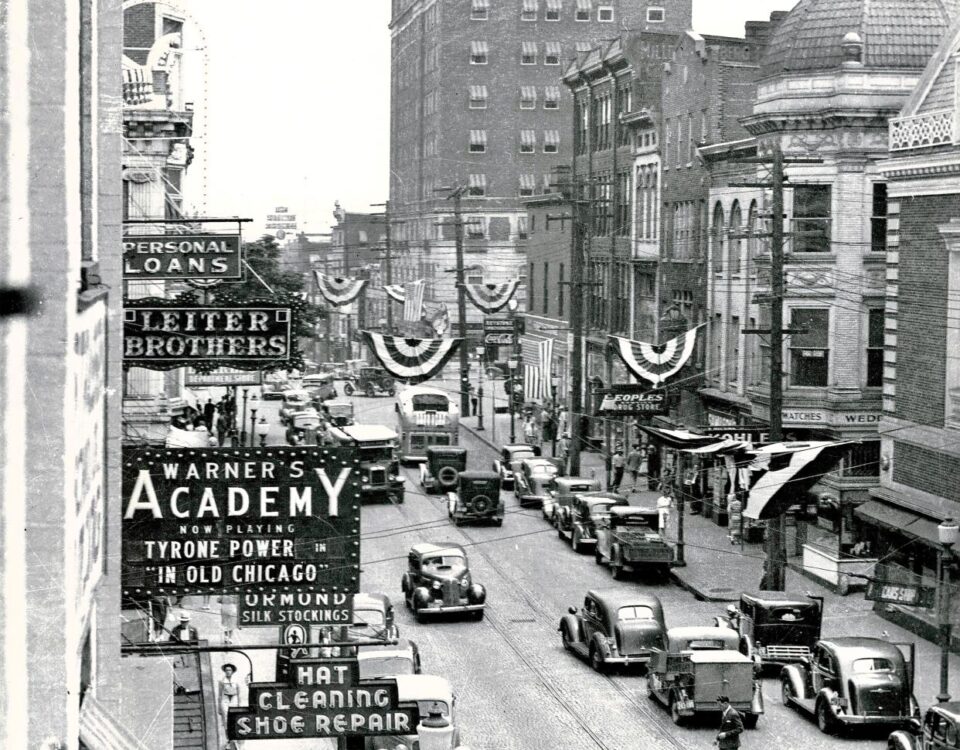

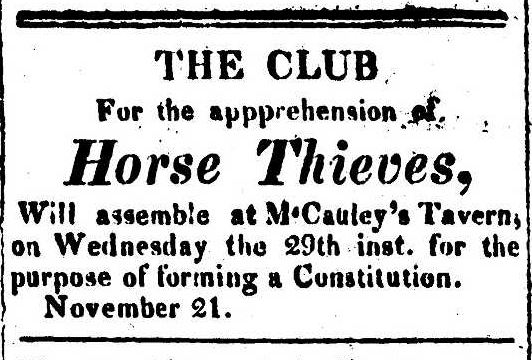

By 1820, the Washington County Association for Detection of Horse Thieves had morphed into the Club for the Apprehension of Horse Thieves. Members organized a meeting at the Washington County Courthouse in October to formalize their rules and regulations. On Nov. 29, the club met at McCauley’s Tavern on Hagerstown’s Public Square (near the present Cannon Coffee), and formed a constitution.

‘The affliction is becoming most grievous’

But of course, horse thieves persisted. On Dec. 2, 1830, the Torch Light & Public Advertiser warned readers, “particularly the female sex,” of the notorious horse thief, John Farrow, who had come to Sharpsburg from the Shenandoah Valley on a stolen mare.

Farrow was described as “about six feet high, slender made, light hair, fair complexion and blue eyes, active upon his feet.” Farrow was known to “boast of his activity and manhood,” and he wore a “blue cloth frock coat of fine cloth,” as well as guilt buttons and a ruffled shirt.

Horse theft continued to plague inns, taverns and mills, where county locals or travelers secured their horses at hitching posts or in stables only to return and find them gone. No turnpike was safe, from Cumberland to the old turnpikes that became U.S. 11 and 40.

The chaos of the Civil War created an alarming increase in horse theft, from thieves impersonating soldiers, to soldiers stealing horses themselves. By this time, the local anti-horse theft association had rebranded as the Horse Thief Protective Association, but its efforts were in vain.

“Cannot something be done to rid the country of such thieving scoundrels?” the editor of the Hagerstown Mail implored on Aug. 26, 1864. “The affliction is becoming most grievous, and our suffering farmers ought to be protected.”

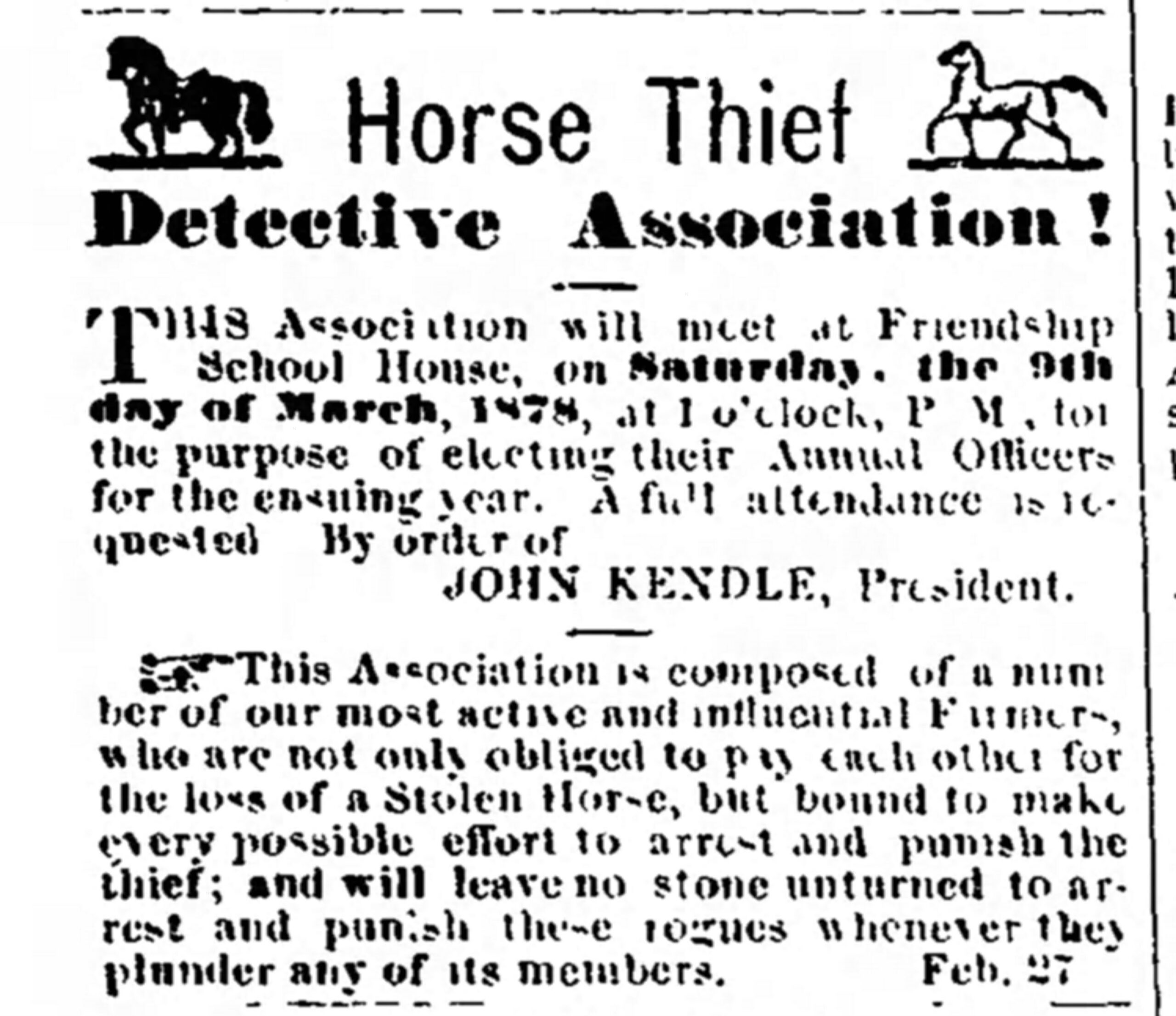

By 1878, the renamed Horse Thief Detective Association was led by President John Kendle, with meetings held at the Friendship School House on the pike from Hagerstown to Williamsport (U.S. 11).

Organized horse thieving gangs persisted into the late 19th century. In 1884, a band of horse thieves hit the Horst, Hershey and Zeller farms west of Hagerstown all in one night, stealing multiple horses and a buggy. A toll-keeper on the turnpike recognized the gang as they galloped by, horses and buggy in tow.

The advent of the automobile in the early 20th century coincided with the decline of anti-horse theft associations. By the 1930s, local horse theft prevention agencies began disbanding.

Horse theft convictions continue even today, but the age of the western Maryland horse thief has ended.

Abigail Koontz is the curator for the Washington County Historical Society. Visit washcohistory.org or call (301-797-8782) for more information.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail: Thefts give rise to the Association for Detection of Horse Thieves