To learn more about Black history in Washington County, trace the experiences of a family

Article Author: Abigail Koontz (This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail February, 2024)

In 1866, Samuel and Amanda Clark traveled north from Virginia into Maryland with their younger sons.

The Clarks, a young Black couple, settled first in the Bakersville area and then in Sharpsburg. They built lives amid the turbulent events of the Reconstruction era in a country still grappling with the atrocities of slavery.

The Clarks’ story is integral to understanding the history of Washington County and the Miller House, home of the Washington County Historical Society.

By 1870, Samuel and Amanda (Jackson) Clark had settled in Bakersville, just north of Sharpsburg. Samuel, 35, and Amanda, 38, were raising a family that included three young sons — William, 8, Samuel Jr., 5, and Edward, 4.

Samuel and Amanda were born in Virginia in the early 1830s; William and Samuel Jr. were also born in Virginia. Edward, their youngest son, was born in Maryland around 1866. It is difficult to determine whether the Clarks had been enslaved before the Civil War ended.

Although census records can be inaccurate, Edward’s birth date creates a timeline for the Clarks’ journey to Washington County during a pivotal time in American history, just after the Civil War’s end in 1865.

The Clarks settled in Western Maryland during the Reconstruction era, which lasted from 1865 to 1877. During this time, the federal government attempted to rectify slavery as it reintegrated the 11 former Confederate states. Despite legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866, affirming that all citizens — including African Americans — were equally protected by law, previously enslaved Black citizens still faced many of the same inequalities and suppression of rights.

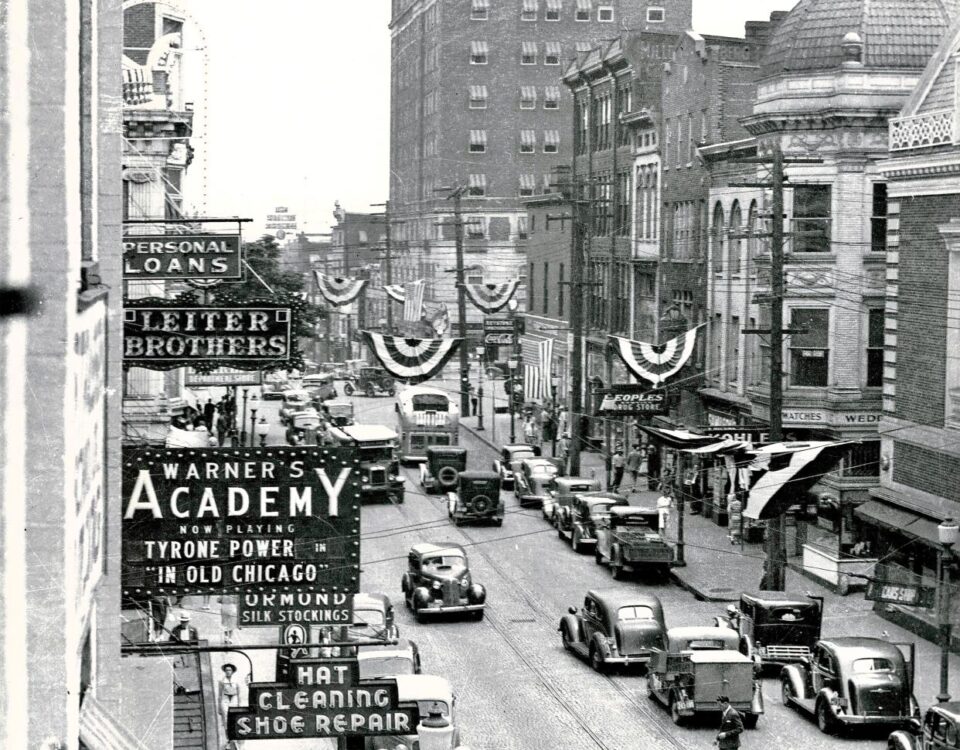

Washington County grows — and so does the Clark family

By 1880, Washington County’s population was 38,561; of those, 3,066 were Black residents. The Clarks had moved to Sharpsburg by this time, and their family of five had grown to 11, including seven sons and two daughters — Rhoda, 8, and Lucy, 1. Samuel and Amanda’s two oldest sons, Charles, 23, and George, 22, had finally joined their parents. Samuel and his sons worked as farm laborers, and the census taker recorded that the seven oldest Clarks could not read or write.

In the 15 years following the Civil War, the Clarks had named two younger sons after Union generals. Amanda gave birth to General Burnside Clark in 1875, named after Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, followed by Sheridan Clark in 1879, named after Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan.

At the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Burnside had led the IX Army Corps in taking a bridge from Confederate soldiers under Brig. Gens. Robert Toombs and Henry Benning. The bridge, called Lower or Rohrbach’s Bridge, is now known as Burnside Bridge.

A younger generation makes its mark

The Clark children grew up in Sharpsburg amid the Jim Crow era and segregation. They would later live in Funkstown, Williamsport and Hagerstown. Two of them became members of Hagerstown’s two oldest Black churches, marrying and creating their own families.

Burnside Clark eventually lived Hagerstown. By 1900, he had married Annie (Terrel) Clark and lived at 14 Blooms Ave. He worked as a waiter and Annie worked as a cook. They had two daughters, Marian in 1900 and Edith Mae in 1903. As teenagers, Marian and Edith worked as domestic servants in private family homes.

By 1918, Burnside worked as a janitor at the Washington County Free Library. The census recorded that Burnside could not read or write, but his wife and daughters could.

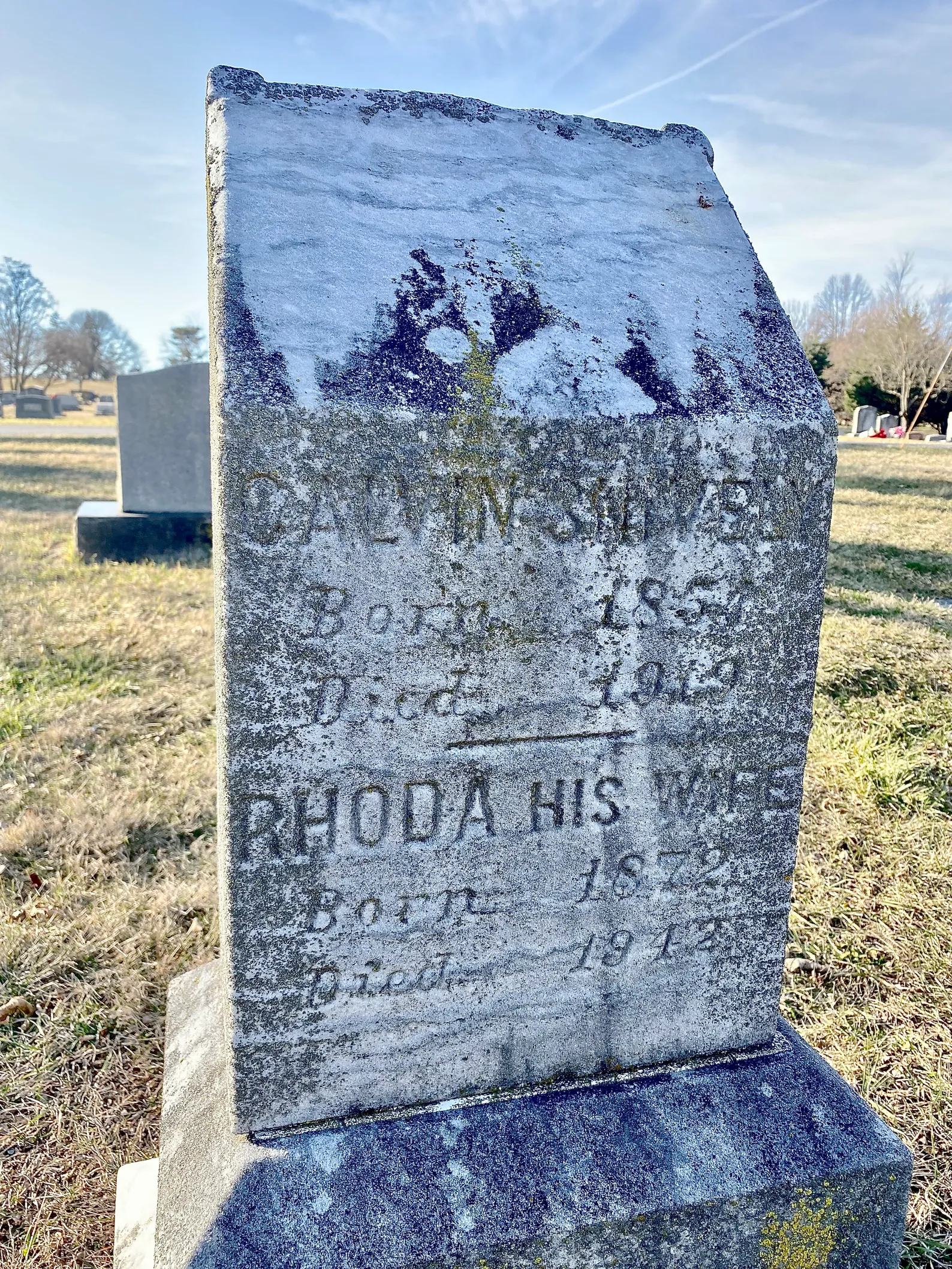

Burnside’s sister, Rhoda, married J. Calvin Snively in 1893. They lived in Funkstown and later Williamsport, with Calvin working as a day laborer.

Rhoda, widowed in 1919, began working as a domestic servant in the home of Dr. Victor D. Miller Jr. at 135 W. Washington St. — now the Washington County Historical Society’s headquarters.

According to the Miller House’s historic structure report, Rhoda worked as a cook for the Millers; the 1930 census listed Rhoda’s occupation as “servant.” Rhoda’s bedroom and bathroom were located above the original 1825 kitchen at the rear ell of the townhouse. According to Rhoda’s obituary, she lived with the Millers (Victor, Nellie, Victor Jr., Helen and Henry) for nearly 25 years.

Rhoda witnessed the woman’s suffrage movement, culminating in the 19th Amendment’s ratification in 1920, but with Jim Crow and voting restrictions, it was many years until women of color could freely and safely vote. For both Rhoda and Burnside, the 1960s Civil Rights Movement was too far away.

Rhoda died on Oct. 17, 1942, at the Washington County Hospital. Her obituary notes that she was “born and reared in Sharpsburg, the daughter of Samuel and Amanda Jackson Clark,” and that she was a member of Asbury Methodist Church and the Ladies Aid Society. She was buried with her husband, Calvin, in Rose Hill Cemetery.

Asbury Methodist Church at 155 Jonathan St., Hagerstown, was founded in 1818 and the first Black congregation in Hagerstown. Burnside attended Ebenezer A.M.E. Church, the second oldest Black congregation in Hagerstown (founded 1820) not far away on Bethel Street.

Burnside Clark died at his home, 342 Jonathan St., on May 25, 1945. He was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery near his sister Rhoda.

The Clark family’s story is woven into the history of Washington County, from Samuel and Amanda’s journey north after the Civil War, to a life in Sharpsburg during Reconstruction. Their history is important in telling a fuller story of Washington County, and Rhoda’s story is vital for a deeper understanding of the Miller House.

WCHS hopes to continue preserving stories of Washington County’s Black residents during Black History Month and into the future. We’re also looking to find a photograph of Rhoda (Clark) Snively for our records; please email curator@washcohistory.org or call the WCHS offices at (301) 797-8782 for more information.