Article Author: Abigail Koontz (This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail May, 2024)

Hats have long fulfilled many roles, from functionality to symbols of self-expression and social status.

One iconic hat of the last two centuries is the top hat. Two 19th-century silk top hats in the Washington County Historical Society’s collection offer glimpses into early local hat manufacturers — particularly the hatter George Updegraff.

When top hats emerged in the 1790s, descending from earlier styles like the 17th century Pilgrim hat, they were made from felted beaver fur. Beaver felt top hats were initially expensive status symbols, but they were also functional, as beaver fur shed water.

Beaver fur was so popular the European beaver population had been depleted by the mid-1600s. French fur traders sought beaver pelts in North America, trading with native populations for furs or hunting down beavers along rivers.

Trappers moved further west, decimating beaver populations and spreading malaria through native populations, until reaching California by the 1820s. As pelts flooded American markets, the prevalence of American beaver felt top hats grew, influenced by European fashions.

Washington County was no exception. On Aug. 12, 1823, the Maryland Herald announced that the hat manufacturing firm, Updegraff & Gilbert, “Have just received a supply of Grand River Beaver, and other FURS, which they will manufacture into HATS.”

The date was a special one for co-owner George Updegraff, 25, as it was both his birthday and the opening day of his new firm on Public Square.

George Emanuel Updegraff was born in 1798 to Peter Updegraff, owner of a Hagerstown bakery. George entered into hat-manufacturing in his early 20s, and by 1823, Updegraff & Gilbert offered the latest styles, including beaver felt top hats.

The beaver felt manufacturing process was lengthy. Beavers were trapped and skinned, their pelts stretched taught for transportation to eastern cities like New York, Boston and Hagerstown.

Haberdasheries and millinery shops received the pelts, still containing beaver fur. Hatters removed longer hairs, called guard hairs, exposing a second layer of softer fur. Hatters plucked this fur from hides and mixed it with a concoction of mercury and acids, breaking down and binding hairs together into a felt-like material.

Hatters washed, carded and pressed this material over cone-shaped molds, shrinking the material before the full felting process began. They molded beaver felt over hat blocks into desired styles before dyeing the felt, cutting the brims and trimming the hats.

Their use of mercury exposed them to its poisonous attacks on their nervous systems, causing shaking hands, eyelids and limbs, and altered speech (thus the origin of Lewis Carroll’s “Mad Hatter”). But no direct evidence suggests George Updegraff suffered such effects.

His wife, the former Eliza Boyd, had their fourth child, William, on June 22, 1831. William began working with his father at age 11 and later apprenticed with another Hagerstown hatter, A. J. Downey. At age 23, William left Hagerstown for Baltimore, joining the hat manufacturing firm of Updegraff, Deveau & Company.

In Hagerstown, George had acquired the space at 49-53 W. Washington St. for his business, Updegraff Hat and Cap Emporium, and later Updegraff & Co. By March 1854, George advertised his first silk hats — perhaps influenced by the fact that his son’s firm in Baltimore specialized in silk hats.

Decimated beaver populations led to the rise in popularity of silk top hats, which were more affordable. Silk top hats were made from “silk hatter’s plush,” which mimicked beaver felt. Hatters applied silk plush over stiffened fabric or boards, shaped into various designs.

The WCHS collection contains an Updegraff & Co. top hat, manufactured circa 1850. Made of a smooth, silk plush exterior over stiffened board, it features a 7 1/4-inch crown. The brim is trimmed with narrow black grosgrain ribbon; the crown’s green silk lining features an Updegraff & Co. label stamped in gold.

Top hat crowns reached their apex by the 1850s, averaging 8 inches tall with a narrow brim. Abraham Lincoln enjoyed this style, called the stovepipe, and kept notes inside his hat. Top hats had first emerged as status symbols for the wealthy, but developed into popular headwear for many.

George Updegraff led a busy life outside making hats, serving as Hagerstown’s postmaster and participating in the First Hagerstown Hose Company and Hagerstown Literary Society. By 1856, his health began to fail, and he stepped back from his business. William returned to Hagerstown to run it, rebranding as George Updegraff & Son.

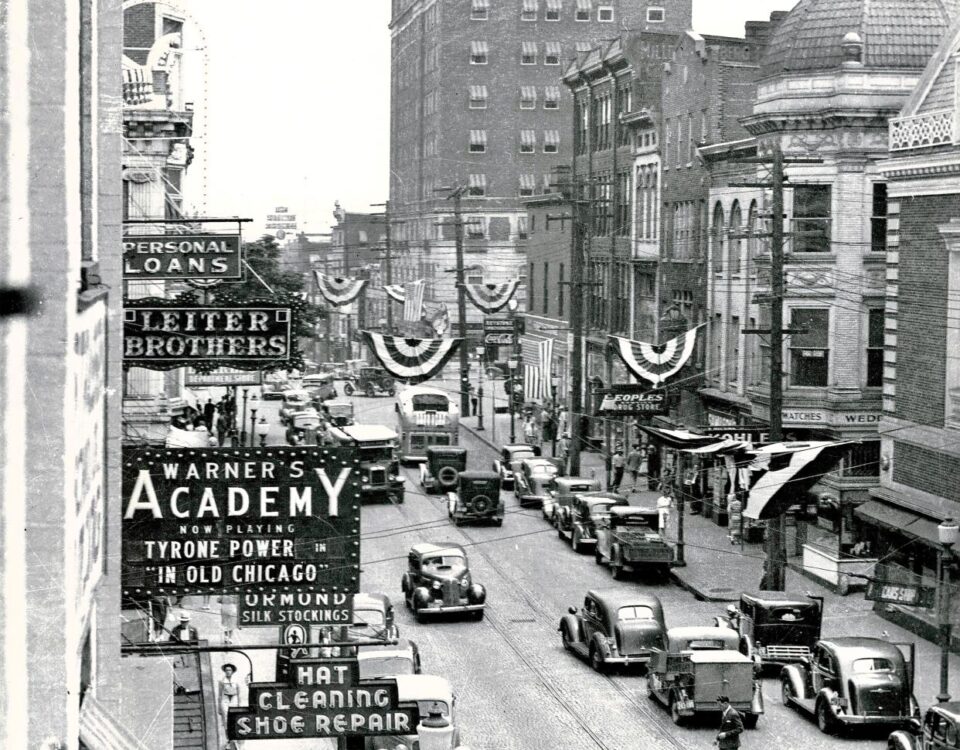

When Brigadier General John McCausland and 1,500 Confederate soldiers reached Hagerstown on July 6, 1864, the store was at the heart of the action. McCausland ransomed Hagerstown for $20,000 and 1,500 sets of men’s clothing, threatening to burn the town if residents and merchants failed to meet the demand.

McCausland demanded “1,500 hats” as part of the 1,500 clothing sets. The Updegraffs had stayed in Hagerstown as Confederates approached, unlike other merchants who fled, and lost their entire inventory. Hagerstown resident Sarah Bell Hall recalled that “[Confederate soldiers] took all Mr. Updegraff’s hats, even the one he had on his head.”

But none had such an enduring legacy as George Updegraff, who died on Aug. 10, 1869. William carried on the company, expanding to manufacture gloves and to open factories in New York. By 1879, Updegraff’s produced 6,000 gloves and mittens annually, selling hats, clothing and furniture locally.

Today, you can spot the original Updegraff advertisement sign on the side of 51 W. Washington St., recently repainted as part of the building’s transformation into apartments. To learn more about the WCHS collection and support our mission to preserve Washington County’s history, visit www.washcohistory.org.