Death was big business in Gilded Age America

There is a fairly common conception that the Victorians were obsessed with death. Plenty of historians devote their careers to the study of the infinitely complex social code surrounding Victorian mourning at the height of its popularity, and some of the most popularly known artifacts from the time period are pieces like memento mori, hair jewelry, or other remembrance pieces. But, as a very smart friend and colleague of mine recently mentioned, Victorians were not obsessed with death. It simply was a very constant reality of life for them, and we tend to judge Victorians based upon the surviving things they left behind. Can you imagine if someone from 2118 were to try to figure out our culture from our social media feeds? What they would come up with would likely not be flattering towards us at all (at least Victorians did not broadcast their awkward teenage phases.) The crucial element in looking at cultural fashions is to give them social and historical context. So let’s do just that!

Mourning has been a crucial part of every culture since prior to recorded history, even though those cultures may mourn in completely different ways. Humans simply need to be able to find closure and work through grief in the aftermath of the loss of a loved one, and the societal traditions surrounding death and burial help the friends and family to process those feelings. The mourning rituals that we’ll be focusing on for now, though, are shared traditions between the United Kingdom and the United States of America. I’ll be referring to Victorian traditions in Gilded Age America, which may sound a bit confusing. To put it simply, while they’re the about same time period and share a lot of social similarities, they take place in two different countries, so they’re called different things. The Victorian Era or period denotes the time under the reign of Queen Victoria in the United Kingdom. The Gilded Age refers to a similar time period in America, which was influenced greatly by British trends. Both periods are marked by times of prosperity, relative peace, and the rapid development of modern industry and technology.

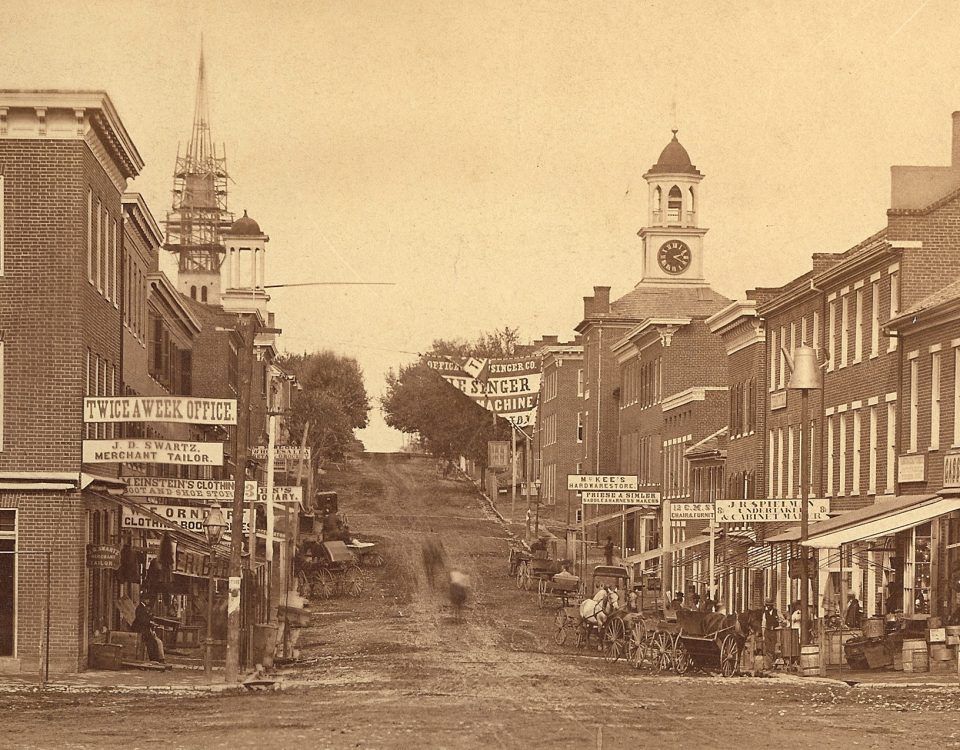

To better understand the mourning culture that develops in late 19th century America, we need to go back to the Civil War. Over 600,000 Americans were killed during the Civil War, making it the war with the highest number of American casualties in our entire history. This meant that many families sent their loved ones off to fight and never saw them again. The war left an entire nation grieving and attempting to find ways to express these feelings. This is in addition to the normal losses from accidents and diseases which could be cured or treated by modern medicine. Many historians believe that children born in the 1880s only had a 20% chance of making it to their 5th birthday, as infant mortality rates were quite high. In addition to the already high rates, the Washington County region suffered higher than average rates of waterborne diseases like cholera and dysentery, as well as diseases like yellow fever, which were carried by mosquito. Losing a child, or even an entire family, to an outbreak of disease, was not an uncommon occurrence in the late 1800s. Loss, and the associated mourning process, were simply a part of everyday life for a Gilded Age American.

The emerging technologies of the late 1800s completely changed the face of mourning, much of which was influenced by the already complex system used in Victorian England. The idea of an open casket viewing, often held in the parlor or sitting room, was already an old tradition, but the advent of rail travel made it possible for distant friends and relatives to attend a viewing, as well as a funeral service. Further enabling the process was the popularization of embalming which occurred during the Civil War. Chemicals like arsenic and formaldehyde could greatly slow the process of decay, allowing those traveling relatives time to visit before burial was made necessary. As a result, the time between death and burial started to stretch.

The observance of a mourning period in dress and social habits was also shaped greatly by the period’s new advances in industrial manufacturing. Plain clothing in the color black was an established tradition among European populations as far back as the Roman Empire, with the exception of pure white for European queens. The length of the mourning period varied widely from culture to culture, and depended also upon your religion and your relationship to the deceased. At the height of the Victorian period, mourning went through several stages, requiring several sets of garments. As mourning rituals became more complex, a booming industry developed around providing all of the accessories that went along with mourning.

For those who had the means and the time to plan out a mourning closet, bespoke clothing would be made by a local tailor or seamstress. As the mourning period typically lasted from six months to several years, and required several sets of new clothing, this was a considerable expense for families. But the alternative was worse. For those who did not have the time or money to put together the needed clothing, the only option was overdyeing existing outfits black, a process which made clothing smell awful and could contain dangerous chemicals.

As industrialization began to impact the clothing industry, an interesting trend emerged: ready to wear fashion. While going to the store and buying clothing is the norm now, it was extremely unpopular when department stores first began to bring in pre-made dresses and suits. However, it did take off in one segment: the mourning industry. Entire stores popped up to supply the great demand for mourning fashion, including stores in downtown Hagerstown. By 1910, stores like the Bon Ton Millinery, located at 27 ½ North Potomac St. (now part of a city parking deck), were even including mourning veils and other apparel in sales. What further propelled sales was the widely held belief that it was bad luck to keep mourning apparel once the observance period had ended. Given the high death rates, this meant that the stores were constantly supplying mourning garments, and could count on repeat customers.

And there was another new technology which found great support among Gilded Age Americans seeking to commemorate a lost loved one: photography. Many of the items we associate with the ‘creepier’ side of Victorian mourning, like hair jewelry or hair wreaths, gain popularity in the days prior to the advent of widely available commercial photography. But in the years after the Civil War, and the development of glass plate photography, it became feasible for many more Americans to afford to take family photographs. In fact, by 1895, Hagerstown was home to five photography studios. The popularity of memento mori images, in which a photograph is taken of the dead, often in a lifelike position, can be explained by this trend as well. In the years when photography was prohibitively expensive, and child mortality rates were so high, many children did not survive long enough for a family photograph. But, photographers were still able to embalmed corpses, giving these bereaved families at least one image of their child to remember. In some cases, these images were the only photographs that the family could afford. As photography technology advanced to the point of hobby photography, this trend began to die out. So while we may judge the Victorians for the habits which seem weird to us in retrospect, the people living in that time period did not have the advantage of our modern technologies, which allow us to capture images and memories of people throughout their lives. They simply had to make due. And hopefully, one hundred years from now, our descendants will stop to put our weird habits into context before judging us too harshly.