As we head into the tail end of an unseasonably cold and windy March, I am reminded of the old adage: In like a lion, out like a lamb. This March, however, seems to be lionesque in its coming and going. Which is somehow fitting for the month in which we most celebrate women. March serves not only as Women’s History Month, but also hosts International Women’s Day. And as we near the centennial anniversary of American women’s suffrage, it is wonderful to see that women’s rights and women’s issues are again having a big moment in the public spotlight. History is full of lionesses masquerading as lambs, and in the spirit of the month, I’d like to shine a little light on some of the local lions who roared.

Mary Lemist Titcomb is a name which should be familiar to local book lovers. For those unfamiliar with Titcomb, she was the elemental force behind the Washington County Free Library, credited with bringing the bookmobile to the area and setting up a lasting legacy for the library’s success. But not many people know just how hard she had to work for her accomplishments. In contemporary times, the county library often forms the backbone of a community, providing not just education and entertainment, but community space and a multitude of services for those who need them. This has not always been the case. Have you ever wondered why the library’s name includes the word ‘free’ in it?

The concept of the modern lending library is relatively new. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, libraries functioned on a subscription basis. Patrons would pay a fee for access to the books, which were carefully curated. Early libraries were often patronized by wealthy families – the careful curation appealed to mothers and fathers who wanted to ensure their daughters were only reading ‘improving’ materials. The subscription fees put patronage out of the reach of the working class, who were also limited by their basic or even nonexistent literacy. Prior to compulsory school attendance, it is estimated that only 50% of working class Americans were literate. Those who could read often relied on daily newspapers or the extremely cheap pulp novel. It is not so hard to understand why most 19th century Americans thought of both books and reading as a luxury available to the rich and idle.

Into this climate came Mary Titcomb. Hired just after the formation of the library in 1901, she would not only have to build up the new library’s collection, but prove its worth to a population that did not need or want a library. She quickly set about changing the mind of the county’s citizens. By focusing on information and education for all, she started to turn the tide of public perception. Before the 1904 introduction of the first book wagon, she had already established rural depository boxes – similar to today’s little free libraries. But she still was not satisfied, sending out the book wagon to the furthest reaches of Washington County, and replacing it with a motorized bookmobile once cars became more widely available. Titcomb also saw the value of the library to the county school system. Once school attendance became compulsory in Washington County in 1916, Titcomb linked the two inseparably together.

But still, Mary Titcomb was not finished improving the lives of the people of Washington County. Around this time, young women were starting to leave their parents’ homes not to get married, but to work and live independently. Recognizing that the daughters of local farmers and factory workers would not have the same access to training as women in more urban areas, Titcomb set up a subsidized training course for young women to become librarians. The program eventually would be linked to a certified college, providing the women with college credit as well as the means to become self-sufficient.

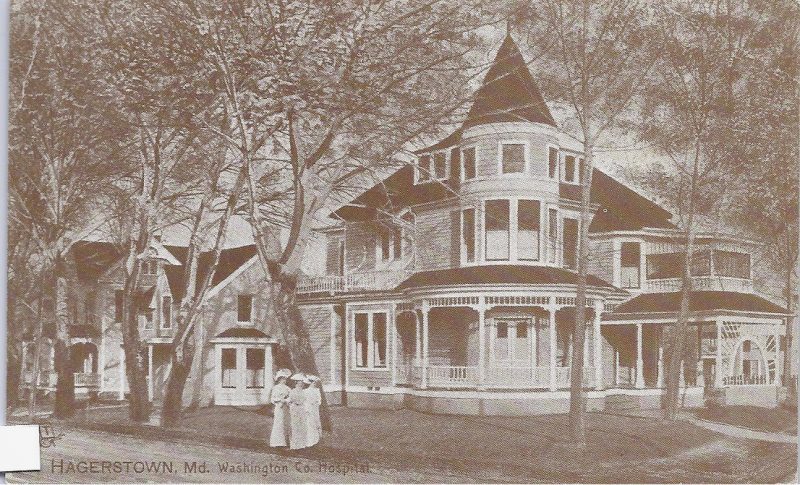

Mary Titcomb was just one of the women in Washington County fiercely fighting to improve the lives of its citizens, and to improve the circumstances for young working women. The Washington County Hospital, founded in 1905, recognized the important role that the county’s women would play from the very beginning. Edward Mealey, who also helped to establish the Washington County Free Library, was known to have spoken greatly on his belief that hospital doctors relied heavily upon their nurses – if the hospital were a body, he likened, doctors might be the brain but the nurses were certainly the hands and feet; in essence, nothing would be done at a hospital without its nurses.

This was quickly put to the test. The hospital board hired M. Grace Matthew as its first Superintendent, with Avis G. Hall serving as her assistant. The two were tasked with not only running and overseeing the hospital, but establishing its nursing program. While the first class contained only 3 students, Matthew and Hall developed a strict but intensive and comprehensive curriculum. All 3 students completed the program and graduated in 1909, by which time, the work of Matthew and Hall had grown the hospital to a point where it needed to move into new, larger accommodations. By coincidence, the new hospital moved into the former Kee Mar College building, which had housed women’s educational institutes since the mid-1800s.

The nursing program, better known as the Washington County Hospital School of Nursing, established itself as one of the premier medical training programs on the East Coast. Until its close in the 1970s, nurses continued to receive the same comprehensive education, which included practical work in the hospital itself. Graduates from the nursing class would serve in medical and administrative roles at home and abroad during both World Wars and spearheaded medical responses to crises like the Spanish Flu in 1919. While the rules for student and active nurses were extremely strict, the school and the hospital provided training that made young women self-sufficient and aware of their own agency.

Mary Titcomb, Grace Matthew, and Avis Hall are just a few of the many ferocious women who actively made society better for all of Washington County’s citizens, but especially its young women. By inspiring confidence and independence, these women would inspire their own young women to take on new roles and fight for change in the area. Washington County is currently home to a huge number of wonderful women, and it’s up to them to now create their own lasting roar.

- The first graduating class of nurses from the Washington County Hospital (c.1909)

- The first Washington County Hospital, located on the corner of Potomac and Fairground Aves. in Hagerstown. (c.1905)

- Mary Lemist Titcomb, one of the first librarians of the Washington County Free Library.